“Okay, Tia,” the teacher said. “I want you to close your eyes right now. We’re going to play a game.”

I looked on as my daughter compliantly squeezed her eyes shut. We were sitting in the kitchen with a retired second grade teacher who is giving Tia a few tips and tricks to strengthen her reading comprehension. One of the things she noticed right away was that my daughter (a realist, and about as literal a child as they come) was not connecting the the text she was reading.

“Now,” the teacher said gently. “The characters in this story are named Bob, Tom and Jack. Tell me, Tia. What does Jack look like?”

“Now,” the teacher said gently. “The characters in this story are named Bob, Tom and Jack. Tell me, Tia. What does Jack look like?”

Tia opened her eyes and looked at the teacher in surprise.

“Close your eyes,” the teacher reminded her with a smile. “I want you to use your imagination and tell me what you think Jack looks like. What is he wearing?”

“Uuuummmm…shorts and a t-shirt?” Tia asked.

“Okay,” the teacher said with a smile. “What about Tom?”

“Uh…jeans and a long sleeve shirt?”

“And Bob?”

Tia squeezed her eyes tight and I could see her trying very hard to figure out this obscure exercise in imagination. “Um…a long sleeve shirt and shorts?”

That was the best she could do. This is my child who is not imaginative. She is not one to get lost in story, or to play make believe. She never has been that way – it is simply not the way she was wired. All of her play is centered around real life, or around stories she has heard before. She’s not one to make up her own stories, but rather will regurgitate that which has already been told.

I’m okay with this, though I confess that for a dreamer/imaginer like myself, it is sometimes baffling to watch her process the world. How did I end up with a child who can’t find a shape in a cloud, or close her eyes and imagine a world where the sky isn’t blue?

I’ll tell you how – I married a literalist, and she is just like her daddy.

I had to bite my lip from laughing at her that day with the teacher. She seemed entirely befuddled by this little game, and as I explained the nature of her personality to the teacher later, both of us agreed that she will likely struggle less with nonfiction books that fiction.

It’s hard to connect with a text when you can’t really see the pictures in your mind.

That’s not to say we won’t keep trying. It’s a necessary skill that I want her to develop, but it won’t ever come naturally to her.

Yesterday, she and I sat down to work on her reading. She pulled out The Magic Treehouse and slowly began to read. I stopped her after the first paragraph.

“Okay,” I said. “Let’s practice what Miss Eileen taught you. After reading this paragraph what picture do you have in your mind of Jack and Annie?”

Tia looking at me pointedly. “Yeah…that doesn’t work for me,” she said. “When I closed my eyes I could only see black. How am I supposed to know what Jack looks like with my eyes closed?!”

I love that child. I love the fact that she holds nothing back. It can be infuriating and baffling at times, but also a breath of fresh air. We always know exactly where she stands on an issue. If she doesn’t like something, she will tell you. She doesn’t have time to pretend to like it.

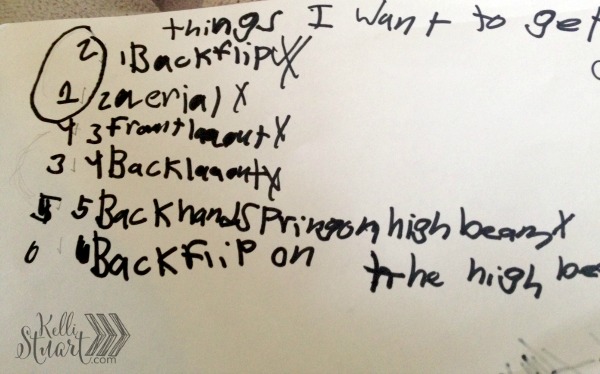

And please don’t ask her to waste time on fantasies. She has too many real dreams to pursue. Like this list of goals she wrote down yesterday.

She’s still a dreamer, you see. Her dreams are simply steeped in the actual world around her.

This is such a cool perspective. I don’t think it would ever occur to me that realists are dreamers too, they just frame it up in light of the world they can feel and experience. Wow. Em is just like that. For months she has been trying to copy the art style of her imaginative sister, but honestly, it just came out looking like she had no drawing skill. Today she showed me her sketch book full of cool fashion designs, complete outfits with all the accessories, and they were EXCELLENT. dragons? No, thank you. Dresses and earrings? She rocked it.

I love that about Em! So cute. 🙂

Tia is so unique and we have known that from the day she was born. She can also say the funniest things, without realizing the humor. She states it matter of fact, in her cute little voice, and makes me laugh. I love that she has big dreams and pray that she will always pursue them. She is beautiful!

Yes. I thought I would wet my pants laughing at her yesterday. The absurdity in her voice was so classic. She really is very unique. 🙂

Didn’t she say it was like a black tv? I am pretty sure she will never be a writer like her mom!

Uh…no. She’ll be something much more practical. Like a lawyer or a doctor. Something tangible and based on fact. 🙂

Our middle son is similar to that. When he was 5 he came downstairs and announced that in spite of the money in his hand he knew there was no tooth fairy. I asked him why. He looked me right in the eye and said “Have YOU ever seen a fairy flying around swapping teeth for money?”

That was the same year he declared Santa to be his parents. All the while his 8 year old brother was still a “believer”. It was a tough season on the 8 year old! 🙂

Ha! YEs – she is definitely more skeptical than both her brothers combined. She is still a believer, though! Just a little longer. 🙂

I really like this post, probably because I’m a lot like Tia. 🙂

Ha! You realists have to stick together, I guess, huh? 🙂