by Kelli Stuart | Like a River From Its Course, Novel, Ukraine, veteran's stories

We sat around a long table inside a very small room. It was hot and loud, all the sounds and smells mixing together in a cornucopia that threw my senses into overload.

They’d made pizza for me, because I’m American and they felt pizza would be a comforting reminder of home.

They weren’t wrong.

I’d been invited to this private meeting because I’d shown such an interest in Maria’s story. I’d peppered her granddaughter, Alyona, with so many questions that she finally offered to bring me to her grandmother so I could ask my questions in person.

As soon as I met Maria, I fell instantly in love, and it wasn’t hard to see why. She was a small woman, her bright silver hair pulled back into a loose bun. Her blue eyes sparkled when she spoke, and the lines that crinkled her face revealed years of tenderness and laughter.

Her family called her Baba Mysa, an affectionate term combining the tender form of “grandma” with a word that translates “little fly.” When Baba Mysa spoke, the room got quiet. We wanted to hear what she had to say, wanted to soak up her grace and wisdom.

As I wrote my story, I knew I wanted to tell Maria’s story, but I also wanted to honor the Maria that I knew – the grandmother who exuded warmth and strength. I wanted readers to know both versions of the same woman.

The character of Maria Ivanovna is loosely based on my Maria’s story of survival during those dark years in the war. But the character of Baba Mysa is based upon the older, wiser Maria who gifted her story to me.

And I fell madly in love with this character.

Baba Mysa’s background and story is entirely fictional, but her mannerisms, humor, and strength are not. Baba Mysa exudes dignity, hope and survival. I adored writing this character because through her I was able to honor the woman who endured indescribable hardships and refused to dwell on them.

Today, I’m sharing a brief excerpt from my upcoming novel, Like a River From Its Course. In this section, Baba Mysa is sharing her story with Luda, encouraging her not to get wrapped up in the pain of the past, but to dwell in the beauty of the present.

For more information on the book, visit the book page where you’ll find more links to some of the history that inspired these stories, as well as Pinterest-worthy images, and links where you can preorder your copy!

Be blessed, friends.

Like a River From Its Course: An Excerpt – Baba Mysa

Baba rocks slowly and rhythmically back and forth in her rocking chair, her hands moving in perfect rhythm. The yarn begins to take shape, a perfect hat for Sasha’s tiny head.

“I want to tell you a story, Luda,” she says. Her voice is soft and warm. I sigh as I melt back into my chair nodding my head in concession.

“I was born a long time ago, deep in the heart of Ukraine. My father was a farmer, and my mother was his strong and doting wife. I grew up among the rows of wheat and vegetables that my father grew.”

Setting her work in her lap, Baba Mysa leans back and a serene look overcomes her face.

“I can still smell the scent of the cherry trees that surrounded our small country house. I feel the cool air of fall and remember every bit of peace as I walked along behind my father through the rows of potatoes. Everything about that time was simple and sweet.”

She pauses, and I look at her impatiently. I enjoy hearing a bit about her childhood, but I don’t understand what she’s trying to communicate.

“When I was ten years old, my father took me into the fields to harvest the potatoes. For hours, we pulled plants from the ground and filled baskets, which we lined up in a long row at the edge of our field. My parents would clean the potatoes later in the day and sell most of them in the local market. At least, that’s what they did every year before this one.”

Baba Mysa’s voice trails off, and I study her face. Her eyes are bright and clear as she stares hard at the wall, the memory playing out before her on an invisible stage.

“On this day, as father and I neared the last row, he told me a joke. I don’t remember what the joke was, but I wish I did, because those were the last words he ever spoke to me.”

My eyes focus in tight as I absorb the shock of her story. Her eyes remain still on the wall, wide and pained.

“As I laughed at his silly words, a man on a large horse rode quickly up to us. He shouted something about danger coming and told us to run. My father told him to take me, and the man scooped me up and fled with me. My last vision of my father is the sight of him standing in the fields, covered in dirt, his arm up in a solitary wave good-bye. I never saw him again.”

It’s quiet for some time as I process Baba Mysa’s story. She wipes her eyes several times, and I don’t speak in order to give her time and space. After a few moments, I finally work up the courage to say something.

“I’m so sorry, Baba,” I say quietly. “I’m so sorry you had to go through that terrible ordeal. But . . .” I pause, unsure of how to proceed without sounding harsh. “I’m just not sure I understand what that story has to do with me,” I say, and then I cringe. The words sound so selfish coming out of my mouth, and I immediately regret them.

Baba Mysa turns her head and studies me closely. She nods in approval at my acknowledgement of, and reaction to, the selfishness in my statement and she waits a beat before responding.

“It has nothing to do with you, child,” she says firmly. “But you can learn from it.” I nod and wait for her to continue, figuring it’s best to remain quiet at this point.

Baba Mysa sighs, and her fingers begin moving in and out of the yarn on her lap once again. “Life is full of heartache and hardship,” she says. “Very rarely will life make sense, and it will almost never seem fair. But if you remember that pain and heartache aren’t unique to only you, that you’re not the only one mired in circumstances that seem too great to bear, you’ll do much better in life.”

©Kelli Stuart

by Kelli Stuart | Like a River From Its Course, Novel, publishing, Ukraine

When I first visited Kiev, Ukraine, I had no idea the magnitude of what they suffered during World War II. As a teenager, I knew very little of the impact of those dark years beyond my borders. Raised with the many stories of our own troops fight for freedom, it never really occurred to me that other countries were impacted far more greatly.

We ambled up a sidewalk one chilly afternoon in March, following our translator, a woman who would later take me into her home for a time and let me call her friend. We stepped up to the monument commemorating the fallen and waited, our breath making small puffs in the cold air.

“This is the site where everything changed for my great-grandfather,” Alyona told us. “In this place, he saw things that you and I cannot even imagine. He never really spoke of that day to us, but my grandmother told me that he was never the same when he returned home.”

Alyona’s grandmother, Maria Ivanovna, would later give me the gift of her story. She trusted me with a small piece of her history, and in so doing, she exploded the borders of the world for me.

Maria’s father, Ivan, was mistaken for a Jew on September 29, 1941, and herded into line with thousands of other men, women, and children, pushed to the outskirts of town, and forced to stand at the edge of the ravine at Babi Yar. By the end of the day on September 30, 33,771 Jews had been brutally slaughtered, bodies piled high inside the gulf the split the land.

Ivan survived.

Just before the gun fired, he collapsed into the ditch where he lay for hours as bodies buried him alive. Under the veil of night, he crawled out.

I will never understand the horror of those days, but I will forever admire the strength and dignity of the men and women who walked through them. In my upcoming novel, Like a River From Its Course, I base many of the characters off the stories of the men and women I met in my years of research.

I pray I’ve honored them well.

In the next couple of weeks, I will be sharing a few excerpts from the book with you, along with some background on how these stories came to be. Today, I share an excerpt from the book in which the character, Ivan Kyrilovich, survives the killing ditch of Babi Yar.

For more information on the book, visit the book page where you’ll find more links to some of the history that inspired these stories, as well as Pinterest-worthy images, and links where you can preorder your copy!

Be blessed, friends.

Like a River from Its Course: An excerpt

Ivan Kyrilovich

“Entering the killing zone is more horrifying than I imagined. Marching in a single-file line, our dignity stripped bare, we slowly wind our way up the small incline to the top of the death ditch.

I try not to look at them, the men and women below, their limbs all tangled in a mass of grief and horror. But the image is too great, so my eyes slowly lower, and when I finally see, my lungs constrict.

The bodies—all intertwined and twisted, thin arms and legs woven in and out in a pattern of heartache—they are the worms I see in my dream.

The sounds around me separate from one another. I hear every movement: the crunch of dying grass beneath trembling feet; the quiet sobs of those resigned to fate; my own hollow breathing as I fight suffocation; Klara whispering her daughter’s name over and over like a lifeline.

“Polina. Polina. Polina.”

I hear the click of German guns as many of them reload, the clanking sound of metal entering chambers. The easygoing banter of the soldiers across the ditch, as if today were just another day at a menial job. All of the sounds reverberate through my mind.

It isn’t just the sounds that magnify. I’m keenly aware of everything. The way the sunlight dapples through the trees, casting brilliant shapes and shadows across the open fields. The warmth of this Baba Leta day on my exposed flesh, fighting against the inner chill that leaves me raw.

I watch a black bird drift through the sky, his wings spread in freedom, gliding through the air without fear. He doesn’t flap his wings, nor does he fight the current of the breeze. He catches it and rises suddenly, sus- pended for a brief moment before leaning to the side and riding the wind to a nearby branch.

All of these things pass through me in an instant, and then it’s over. A German command brings the soldiers forward, their dusty caps set high on their foreheads. It is then that I see him.

He walks briskly down the line to the man stationed across from me. It’s the steely-eyed killer who pushed me into line, the same boy who killed the woman in the fur coat. Leaning forward, he whispers in his comrade’s ear. The soldier glances in my direction, shrugs his shoulders, and steps back, letting the boy with fire in his eyes take his place. I feel the heat, and in my final moments grow emblazoned.

Looking back at him from across the killing ditch, I stare straight into his eyes, feeling a surge of hatred that surprises me.

Ready!

The first command rings out, bursting through the air with a measure of indifference.

Set!

“Get ready, Polina,” I whisper as the Germans raise their guns. Though we’re separated by a ditch, I look directly into the barrel before me. It’s black and cavernous and threatens to swallow me whole. I taste metal, and my ears ring as I await the final command.

Aim!

I wait a beat, then yelp, “Now!” I grab Polina’s hand and crumple just as the shots burst through the air.”

©Kelli Stuart, 2016

[Tweet “Like a River From Its Course, the debut novel by @kellistuart, is now available for preorder! http://amzn.to/1WO5HPB #RiverNovel”]

by Kelli Stuart | Family, Germany, Inspiration, Life, Motherhood, Travel, Ukraine

The building was cold. Drafty would be one way to describe it, but the word wouldn’t do it justice. The heat never worked, and the winter months dragged on. We sat at a long, white table, all bundled in our hats and coats, hands tucked into pockets in an effort to stay warm while the teacher drilled us on the Nominative case, the Genitive Case, and everything in between.

It was 1998, and I was a student at The Institute of Foreign Languages in Kiev, Ukraine. There were seven students in my Russian language class – six of them from China, and me, the blond-headed American with a love for languages and a longing for adventure.

After school we’d attempt small talk. Our only common language was Russian, so if we wanted to converse it had to be in the language we’d come there to learn. We did a lot of gesturing, and a lot of laughing. I’m sure we looked quite comical walking down the street, the Chinese and the American charading our way through Kiev.

On the afternoons when I wasn’t hanging out with my classmates, I’d explore the city on my own. My very favorite pastime was getting lost.

I got lost on purpose.

I’d walk in a new direction and take multiple turns until I didn’t quite know where I was, then I’d make myself find a way back. In my self-induced confusion, I found so many great little treasures.

I stumbled upon a tea shop on one of my wanderings. I walked inside and breathed in deep the heady scent of hundreds of different teas. Glass jars lined the wall from floor to ceiling, all of the labels written in Russian so I couldn’t quite make them out. But oh, how I enjoyed the challenge.

The owner of the shop was an older woman with bright grey hair and piercing eyes that probed my face. She found me amusing, maybe even a little annoying, and after a few attempts at speaking and realizing that my language was not strong enough to keep up with her fast speech, she left me to explore the walls on my own.

Another day, I got so turned around I could not find my way back. It was getting dark, and I was freezing cold. I was twenty, and didn’t always make the best decisions, but I did know that getting lost in a big city after dark on a cold night was a bad idea.

So I hailed a cab.

In Kiev, anyone can be a cab. Stick out your hand and anyone looking for money could swing by and pick you up. I decided to wait until I saw an actual cab car before sticking out my hand. You know, for safety.

I ended up in the car with one of the happiest, friendliest men I’ve ever met. His eyes swam with kindness. He spoke no English, but he was fluent in Spanish. My Russian language was stronger at that point, and I had a small cache of Spanish words stored in my memory from high school, so we pieced a conversation together using Russian and a bit of Spanish.

It’s been nearly eighteen years since I spent that semester in Ukraine, and even now I find that I still long for adventure. I crave that feeling of being lost.

Last year just about this time, I jetted off to Munich for a week with my dad, and on my first day there I took a walk. I turned left, then right, the left again until I was significantly turned around, and my heartbeat quickened. I was lost, and I was thrilled.

There’s beauty in wandering, and comfort in adventure. Sometimes it’s scary, not knowing where the next turn will lead you. But if you’re willing to take the ride, to seek out the treasures in the unknown path, you just may find that the unknown is the place where your soul comes alive.

[Tweet “There’s beauty in wandering, and comfort in adventure.”]

Some days, I feel swallowed up by the predictability of my life. Each day, though hectic, is relatively the same. We wake up, we have sports and school and bickering and loving, we go to bed, and we wake up and do it again.

I’m not complaining. I love my life. It’s messy and beautiful, and I wouldn’t want to walk this path with anyone besides the people I’ve been given. So in the moments when I find myself longing for adventure again, I look at the unknown that stands before me.

Though my schedule may be predictable, the truth is I don’t know which direction tomorrow will lead me or my family. It’s always a matter of putting one foot in front of the other, and looking for the adventure that is right now.

Even today, it’s possible to get lost on purpose. The fun lies in exploring each new turn life throws our way.

Are you an adventure seeker? How do you find adventure in the mundane spaces of life?

by Kelli Stuart | News, Novel, Ukraine, veteran's stories, World War II

She sat across from me, her mouth turned up into a soft smile. With eyes crinkled at the edges, and a gentle lilt to her words, she took me back into the recesses of her memory.

It was 2003, and I was in Vinnitsya, Ukraine. Elizabeta Yepifanova agreed to meet with me on a brisk, March morning, and over a spread of tea and chocolates, she invited me into her story.

Elizabeta was sixteen when the Nazis invaded Vinnitsya. Unable to enlist in the Red Army, she found herself stuck, forced to live under the invader’s imposed law, and unwilling to stand idly by while young boys with cropped hair took over her home. She wasn’t, of course, the only one left heated with indignant pride.

A group of young men and women like herself formed a quiet group. Meeting weekly in the hushed corners of the local library, this pack of partisans made it their mission to fight a different kind of battle with the Nazis.

“We fought a psychological battle,” she told me. The interpreter sat quietly by my side, whispering Elizabeta’s every word like it was a sacred secret, and perhaps it was.

“We wanted those boys to know that though they had physical might, they did not have the power to break our spirit.” She tossed me a mischievous glance. “And we won that psychological battle.”

Not content to subject themselves to the Nazi’s rules, Elizabeta and her comrades devised secret plans to keep the German soldiers ever aware of their own infallibility. “The Germans were afraid of us,” she laughed. “We were unpredictable and shrewd. They never knew where we would strike next.”

“I got very close to a Nazi once,” she continued. “It was the most dangerous mission I participated in. But I was successful. Of course I was successful,” she chuckled. “I’m here talking with you now!”

Late one evening in 1943, Elizabeta and her friend, Sophia, walked to a nearby market where German soldiers were known to congregate, and they openly flirted with two of the Nazis.

“We got those boys to come with us easily,” she said, eyes twinkling. “We didn’t speak German, of course, and they knew very little Russian, so most of the communicating took place with gestures. But if you can believe it, I was quite beautiful then, so it didn’t take much to convince them to follow us.” I smiled, because I could believe it. Behind the wrinkles and the grey hair, Elizabeta Yepifanova had striking features.

“We lured them to our safe house and had them take off their coats in the front hall. When we saw their guns, we pretended shock and fear, and those boys were quick to remove the weapons and lay them down. They thought they’d get something from us that night, but we were the ones who got lucky.” With a slap of the knee, Elizabeta let out a hearty laugh.

by Kelli Stuart | Novel, Travel, Ukraine, veteran's stories, World War II

“It’s not fair! You’re just…you’re putting to much pressure on ME!”

With face in hands, the child ran from the room and slammed the door leaving me bewildered in the kitchen. All I asked was for help putting the dishes away.

Too much pressure?!

With a shake of my head, I left the dramatic child alone for a few minutes, because we both needed a time out. I pulled the box of old photographs down off the shelf and began rifling through. Sometimes memories bring a soothing balm to the rocky places of the present day.

When I came across the pictures from my trip to Ukraine in 2003, I let out a little yelp of joy. I’d been looking for those pictures for weeks, wanting to jog my memory of the events that so clearly marked the path for my book. I ran my fingers across the photographs, willing myself to remember the moments.

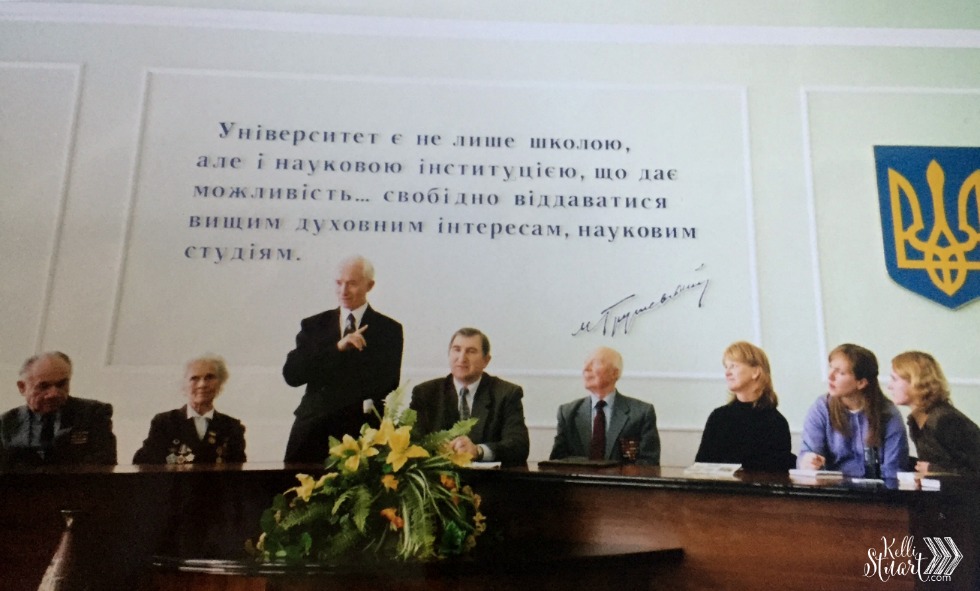

2003: A Meeting with veterans in Kam’yanets Podilsky, Ukraine.

Some of them seemed vague. The time I spent in that country was a whirlwind, and I was rather pregnant great with child, so not all the memories were cohesive. But a few were, and as I sifted through them, my dramatic child came and sat by my side.

“Who’s that?” The voice was soft, with the hint of apology floating at the edges.

“Those are men who battled evil,” I answered. “Those are men who know pressure. Real pressure. They understood suffering.”

I turned and offered a crooked smile. “Those are men who probably didn’t enjoy cleaning the kitchen, either. But they wouldn’t call it pressure. Maybe just more of an annoyance?”

A smile in return. The ice was breaking just a bit.

“Do you remember their stories?”

I looked carefully at the photo. “Not specifically,” I replied, “but I have them all written down. I’ll look them up later.”

“Why are their stories so important?” The innocent question was met with a quizzical stare, and all I could offer was a shrug at that moment. I couldn’t formulate the right answer, so I let the question hang in the air.

“Why are their stories so important?”

Long after the kitchen was cleaned and the house grew silent as the sun set low, I continued to mull over that one, simple inquiry.

Why are their stories so important?

These men are not American. Their stories and experiences tell of not only a time unfamiliar to most of us, but also a culture. Why is it important to tell their stories? Why should you care? Why should I care?

It’s said that the shortest distance between two people is story, and if that’s true then the question we should be asking is why wouldn’t we care?

These men stood up before their peers, and before a strange American girl, and they shared their stories. They shared them because they wanted me to know, and they wanted you to know.

They wanted us to see that the distance between us and them isn’t really all that far after all. We share the common longing for peace in a world that often quakes with violence.

We were all uniquely designed by a common Creator, and that design draws us together even if the miles, the language, and the landscape of our lives looks different.

So why are their stories important? Why should you care about the histories of a handful of men and women from half a world away?

Because their stories offer the connection between then and now, and in a time when evil runs rampant and we watch the world with wide eyes, a reminder of man’s capacity to overcome evil is beautiful, indeed.

Because their stories offer the connection between then and now, and in a time when evil runs rampant and we watch the world with wide eyes, a reminder of man’s capacity to overcome evil is beautiful, indeed.

In the months leading up to the release of my book, I will offer more background on the stories and events that inspired the novel. In the meantime, visit the War Stories page to read the histories of the four people who most impacted me as I researched this novel.

Because their stories offer the connection between then and now, and in a time when evil runs rampant and we watch the world with wide eyes, a reminder of man’s capacity to overcome evil is beautiful, indeed.

Because their stories offer the connection between then and now, and in a time when evil runs rampant and we watch the world with wide eyes, a reminder of man’s capacity to overcome evil is beautiful, indeed.