by Kelli Stuart | Like a River From Its Course, Novel, Ukraine, veteran's stories, World War II, Writing

I spent the better part of two days last week tearing my house apart.

I was on a search for a photo. I could see the picture in my mind, but it wasn’t any of the places I imagined I would have put it. The up side to all this searching was the natural consequence of cleaning out drawers that desperately needed to be cleaned.

I finally decided to check the attic, even though I knew for certain the photo couldn’t be up there. Hadn’t I seen it recently?

I opened the first album I found and gasped. There she was, just as I remembered her, staring up at me with those kind, smiling eyes.

Ladies and gentlemen, I would like to introduce you to the real Maria Ivanovna.

Maria’s story is fictionalized in my novel, though of all the storylines, hers stays truest to the real life plot. Some of it is fictionalized based on other stories that I gathered, but the skeleton of the entire book started with this woman right here:

Isn’t she just lovely?

And as I mentioned in the post about Baba Mysa, that character was also a composite of this real and lovely woman who entrusted me with her story so long ago.

After I found this one photo, I was hungry for more, so I reached out to my dear fried in Ukraine, who also happens to be Maria’s granddaughter, and I asked for more photos.

Alyona took me into her home when I was 20 years old, and she gave me her bedroom for four months so that I could study Russian. Every day, I’d walk from her little apartment on Shamrila Street to the train station, and I’d make the hour long trek to the Institute of Foreign Languages for my classes.

It was one of the grand adventures of my life.

The photos Alyona sent me brought tears to my eyes, because they brought not only the character of Maria Ivanovna to life, but they also gave me more of a visual for the real Maria.

Maria as she was making her escape from Germany.

Maria after the war.

Maria and her husband.

It’s easy to forget sometimes that history is real people. It isn’t just stories. When we’re so far removed from an event that is now immortalized in film, television, and history books, we overlook the before and after of all this history.

Maria had a history before the Germans forced her into slave labor, and she had a future after she returned. She was more than the moment of her captivity. She was real, and she was a delight.

The final picture I found was taken on the night that I met Maria face to face. It was 1996, and we were in Kiev, Ukraine. I had been invited to have dinner at Maria’s place, and while there, she shared her full story with me.

That was the birth place of Like a River From Its Course.

Now, before I show you this picture, I would like to sincerely apologize for what I’m wearing. I don’t ever remember owning such a sweater. It appears I let Mr. Rogers dress me for that evening.

You’ve been warned.

Kelli (in a most unfortunate sweater), and Maria. April, 1996.

History is real people, and as you read my book, I hope you will remember that these are more than just stories. These were lives. These were men and women who refused to be defined by one moment in time.

In the wake of all that’s occurred in our own country this week, it’s good to remember that we are more than one horrific event. We can still learn from history. We can honor the fallen, pick up the pieces, and refuse to be defined by that terrifying moment.

History is real people, and history is happening even today.

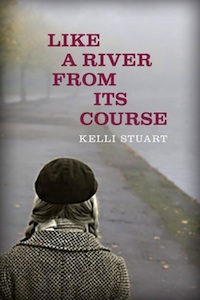

Like a River From Its Course is now available wherever books are sold!*

Like a River From Its Course is now available wherever books are sold!*

Also, if you’ve read the book, would you be so kind as to leave a review on Amazon or Goodreads? Those are kind of a big deal. *wink*

Thanks, everyone!

*affiliate link included

by Kelli Stuart | Like a River From Its Course, Novel, Ukraine, World War II, Writing

Writing a historical fiction novel is daunting.

Setting a historical fiction novel in World War II Soviet Union might just be crazy.

When I set out to write my novel, I wanted to develop a story that was as historically accurate as possible while still offering myself creative license. This proved to be an overwhelming task given the vast history of those years, and the many different conflicting accounts of what happened.

There were times when I wanted to give up altogether.

Other times, I wondered if I should just make it Science Fiction. Hitler could be a Vampire, and all his cronies would be various forms of the undead.

It would’ve been a hot seller, but the premise sounded dumb, so I pressed on.

When it came to writing the Ukrainian characters, the stories flowed (almost) easily. I knew their stories, and so fictionalizing the tale didn’t feel like a chore. But writing the story of Frederick Herrmann, a young Nazi soldier hell-bent on carrying out the mission and task that his country and set before him left me almost paralyzed at times.

I am a bit of an idealist. The actions of the Nazi soldiers was something I couldn’t quite comprehend. How could so many young people follow so blindly the ideology of a clear tyrant and psychopath? How could they kill so robotically? And how did they live with themselves later?

I needed a reason, and so I set out to find one, but the research often led me to images that were so horrific, I had to step away. There were days when I hated Frederick and all that he stood for. I didn’t want to write of such atrocities, because I didn’t want to believe that people could really be that evil.

Frederick is the only purely fictional character in my book. While all of the other characters are based on the stories of men and women I met in Ukraine, Frederick came a little more reluctantly from my imagination.

I fought for Frederick. I wanted to redeem him somehow. I wanted there to be a reason for his wickedness, and in the end I think there was some redemption for his character, though it wasn’t what I expected when I began writing.

I won’t spoil the story for you, but I will tell you that Frederick eventually became one of my favorite characters to write. By the end of the story, I no longer hated him. I pitied him, and I pitied all the boys like him – the real ones who believed that they were right and justified in their mission.

I don’t know what the after effects of the war were for those who pulled the trigger senselessly and brutally. I don’t know how the killings of Babi Yar, where 33,771 men, women, and children were slaughtered in two days time affected the young men who did the killing.

I have to believe that there were lasting effects. I have to believe that for many, though I suspect not all, of those young men, the images that they saw, that were caused by their own calloused hands, haunted them for the rest of their lives.

How could they not?

Frederick Herrmann was a young man swallowed by the ideals of his country, and by a desperate need to please his father. His story may have been fictional, but many of his surroundings and experiences were not. The names of his commanders are the names of actual German leaders in Kiev in those years.

I set out to write a historical fiction story that stuck as close to fact as possible. Though Frederick is fictional, his story is not so unlike many of the young men from those desperate days.

In the end, Frederick became as real to me as any of the other characters.

I know some of you have read the book – what did you think? What are your thoughts on Frederick (without giving spoilers, please!)?

Also – HOORAY! – Amazon has started shipping out books! Have you ordered your copy yet?*

Amazon has also opened up the reviews section of the book, so if you’ve read the book would you consider leaving a review?

Thanks, everyone!

*affiliate link

by Kelli Stuart | Faith, Family, Inspiration, Like a River From Its Course, Novel

We didn’t really know what to expect when we stepped into the house. We only knew it would be a unique experience.

A Nigerian family from our church had invited us to celebrate the 50th birthday of their oldest sister with them. She is visiting America for the first time from Nigeria, and they planned a night of unabated joy.

As the evening wore on, more and more people poured through the doors, all of them dressed head to toe in traditional clothing. The women’s dresses were handmade by one of the sisters, their head wraps bold and bright, heels high, and jewelry big.

We began the evening with a hymn, following by praise songs, words of wisdom from the brother and our pastor, then words of affirmation for the birthday girl from anyone who wanted to speak.

They were effusive in their praise, voices singing loud. No one cared if they were on key or not. It wasn’t about a perfect rendering of the song. It was about praise. It was about joy.

It was a celebration.

“We want to thank God that you are still alive today!” they said, over and over. “We praise God because He could have taken you before today, but He didn’t. He gave you 50 years, and we thank Him for that.”

They pulled out drums and sang, the women all gathering around the celebrated sister, and they danced, laughing and clapping. The younger brother dropped to his knees, his arms raised high to the sky. It was worship. It was celebratory. It was praise.

It was joy.

And I sat in the corner with tears wetting my cheeks because this is the joy I long to fill my home. These people come from a country that has seen deep and lasting hardship, but you wouldn’t know. There was nothing melancholy or solemn about the evening. Only smiles that split wide their faces, and the overflowing joy that comes with praise.

It’s something I’ve seen before. I don’t know why, but I’m forever amazed at the ability of those who have walked through pain and suffering to live in the present with great joy and gladness. But what do I expect?

Bitterness? Anger?

Why do I look for these things in those whose backgrounds have been less blessed than my own? Is it because I’ve been so immersed in the American mentality my whole life that I falsely and wrongly believe that hardship must naturally be dwelled upon?

Is it because I have seen so many people I know, people who have been unendingly blessed, dwell on hurt feelings and heartaches, simmering in anger rather than living in the blessed beauty of forgiveness and joy?

Oh, America. How much we miss when wrapped inside all our ‘blessing’.

We miss the opportunity for joy when we aren’t willing to look past our anger.

We miss true, unadulterated praise when we get stuck dwelling on the heartaches of the past.

We lose sight of every good thing when we constantly look toward an unknown future in fear.

I’m saddened to think that my country is missing out on a great deal of celebration because we’re so blinded by ease.

Easy Street has made us boring.

“In a word, the future is, of all things, the thing least like eternity. Is is the most completely temporal part of time – for the Past is frozen and no longer flow, and the Present is all lit up with eternal rays.” C.S. Lewis, The Screwtape Letters

Our nation is caught up in the uncertainty of the future right now. We’re rolling in our hopes and our fears, and it’s stealing joy, siphoning it right off before our eyes.

We spend so much time looking into the past, hoping that it will dictate the future, that somehow we seem to have forgotten how to enjoy the present, which is bright with the rays of eternity. The present is where love takes shape – it’s where memories are made, life is lived, and joy is found.

[Tweet “”For the Present is the point at which time touches eternity.” C. S. Lewis, The Screwtape Letters”]

Oh, friends. May we all experience the joy of living in the present today. May we let go of the anger and hurt of the past, and fear not the uncertainties of the future.

May we touch eternity today, right now, in this very moment.

If you haven’t preordered your copy of my novel, Like a River From Its Course, what are you waiting for?* It’s based on the true stories of men and women I spoke with personally – people who did not dwell on the past, but who lived joyfully in the present. This is a book you don’t want to miss!

*affiliate link included

by Kelli Stuart | Faith, Family, Like a River From Its Course, Ukraine

It’s no secret that orphan care is near and dear to my heart. It’s something that I care about deeply. Some women long to have children naturally, and cannot, and adoption is the way they grow their families.

I am, admittedly, quite the opposite. I longed to adopt the way that most women longed to have children naturally, and for whatever reason, that door has been closed to me. At least up until this point. The future is always a mystery, though…

After our Russian adoption was terminated, I poured myself into finishing my novel. All of the kids were in school at that point, so I’d drop Landon off at preschool, then drive to the Whole Foods around the corner and have ridiculously healthy food while I tapped away at my computer.

I shed big, giant alligator tears throughout the entire process. I called my husband on more than one occasion sobbing from the parking lot, my heart so utterly torn over this fractured dream. I felt lost and confused.

I was a mess.

Writing Like a River From Its Course* was part of my healing. Through the rhythmic tapping of my fingers, I released some of the inner angst that plagued me. As I dove head first into the heartache of my characters, I was able to dissect my own broken heart.

I grieved as I wrote, and in the end this novel kept the grief from swallowing me whole.

As I prepared to launch the book out into the world, I wanted to find some way to give back to the country that had given so much to me. How could I gift these stories back to Ukraine?

I bathed this in prayer, and the answer came swiftly in the form of a ministry called World Hope Canada.

I first stumbled across World Hope Canada when Lee and I were debating whether or not we should continue to pursue adoption, or accept our family as it was. As I researched, I found Hope House Ukraine, a division of World Hope Canada that ministers directly to young women who have aged out of the orphanage.

The story is long and twisty, and it involves more of me in tears so I’ll spare you all the details, but to cut to the chase, I have fallen in love with the work of this ministry.

Image from Hope House Ukraine

Girls coming out of institutional homes are some of the most vulnerable in the world. They are often very young (many are aged 16-17), under-educated, naive, and they’ve spent much of their life without any direct guidance or supervision.

These young women are highly susceptible to human trafficking, substance abuse, and pregnancy, which only perpetuates a vicious cycle.

Hope House Ukraine is standing in the gap.

Hope House is a place where girls can live after leaving the children’s home. They are given a roof over their heads and tutoring so that they can pass the exams to get into trade schools. They’re taught life skills like how to maintain a home, how to garden and cook, how to operate inside a family, to live under authority, and to take responsibility for their futures.

There are now two fully operational homes in Ukraine, each of which houses beautiful girls who just need to be reminded that they have worth and value in this world.

From the World Hope Canada website: “Our vision for Hope House is to be a loving and supportive home where vulnerable girls can learn family and life skills, and receive an education so they can live successful, independent lives that are honouring to the Lord.”

As I bring Like a River From Its Course to the world, I want to give back to the country that gifted me these stories in the first place. I have committed up front to financially supporting Hope House Ukraine out of the proceeds that come not only from this novel, but from the books to come.

Specifically, I have chosen to sponsor a young girl named Masha in honor of the woman who inspired this book in the first place.

I hope that you will take a little time to look into Hope House and marvel at the work they’re doing in Ukraine. And if you would like to join me in partnering with this ministry, please let me know and I’ll help connect you to the right people.

In the meantime, please know that every time you purchase one of my books you are helping young women in Ukraine know and see their value. Every time you tell someone else about the book, you’re taking part in this amazing ministry.

Thank you for partnering with me in this way!

by Kelli Stuart | Like a River From Its Course, Novel, Ukraine, veteran's stories

We sat around a long table inside a very small room. It was hot and loud, all the sounds and smells mixing together in a cornucopia that threw my senses into overload.

They’d made pizza for me, because I’m American and they felt pizza would be a comforting reminder of home.

They weren’t wrong.

I’d been invited to this private meeting because I’d shown such an interest in Maria’s story. I’d peppered her granddaughter, Alyona, with so many questions that she finally offered to bring me to her grandmother so I could ask my questions in person.

As soon as I met Maria, I fell instantly in love, and it wasn’t hard to see why. She was a small woman, her bright silver hair pulled back into a loose bun. Her blue eyes sparkled when she spoke, and the lines that crinkled her face revealed years of tenderness and laughter.

Her family called her Baba Mysa, an affectionate term combining the tender form of “grandma” with a word that translates “little fly.” When Baba Mysa spoke, the room got quiet. We wanted to hear what she had to say, wanted to soak up her grace and wisdom.

As I wrote my story, I knew I wanted to tell Maria’s story, but I also wanted to honor the Maria that I knew – the grandmother who exuded warmth and strength. I wanted readers to know both versions of the same woman.

The character of Maria Ivanovna is loosely based on my Maria’s story of survival during those dark years in the war. But the character of Baba Mysa is based upon the older, wiser Maria who gifted her story to me.

And I fell madly in love with this character.

Baba Mysa’s background and story is entirely fictional, but her mannerisms, humor, and strength are not. Baba Mysa exudes dignity, hope and survival. I adored writing this character because through her I was able to honor the woman who endured indescribable hardships and refused to dwell on them.

Today, I’m sharing a brief excerpt from my upcoming novel, Like a River From Its Course. In this section, Baba Mysa is sharing her story with Luda, encouraging her not to get wrapped up in the pain of the past, but to dwell in the beauty of the present.

For more information on the book, visit the book page where you’ll find more links to some of the history that inspired these stories, as well as Pinterest-worthy images, and links where you can preorder your copy!

Be blessed, friends.

Like a River From Its Course: An Excerpt – Baba Mysa

Baba rocks slowly and rhythmically back and forth in her rocking chair, her hands moving in perfect rhythm. The yarn begins to take shape, a perfect hat for Sasha’s tiny head.

“I want to tell you a story, Luda,” she says. Her voice is soft and warm. I sigh as I melt back into my chair nodding my head in concession.

“I was born a long time ago, deep in the heart of Ukraine. My father was a farmer, and my mother was his strong and doting wife. I grew up among the rows of wheat and vegetables that my father grew.”

Setting her work in her lap, Baba Mysa leans back and a serene look overcomes her face.

“I can still smell the scent of the cherry trees that surrounded our small country house. I feel the cool air of fall and remember every bit of peace as I walked along behind my father through the rows of potatoes. Everything about that time was simple and sweet.”

She pauses, and I look at her impatiently. I enjoy hearing a bit about her childhood, but I don’t understand what she’s trying to communicate.

“When I was ten years old, my father took me into the fields to harvest the potatoes. For hours, we pulled plants from the ground and filled baskets, which we lined up in a long row at the edge of our field. My parents would clean the potatoes later in the day and sell most of them in the local market. At least, that’s what they did every year before this one.”

Baba Mysa’s voice trails off, and I study her face. Her eyes are bright and clear as she stares hard at the wall, the memory playing out before her on an invisible stage.

“On this day, as father and I neared the last row, he told me a joke. I don’t remember what the joke was, but I wish I did, because those were the last words he ever spoke to me.”

My eyes focus in tight as I absorb the shock of her story. Her eyes remain still on the wall, wide and pained.

“As I laughed at his silly words, a man on a large horse rode quickly up to us. He shouted something about danger coming and told us to run. My father told him to take me, and the man scooped me up and fled with me. My last vision of my father is the sight of him standing in the fields, covered in dirt, his arm up in a solitary wave good-bye. I never saw him again.”

It’s quiet for some time as I process Baba Mysa’s story. She wipes her eyes several times, and I don’t speak in order to give her time and space. After a few moments, I finally work up the courage to say something.

“I’m so sorry, Baba,” I say quietly. “I’m so sorry you had to go through that terrible ordeal. But . . .” I pause, unsure of how to proceed without sounding harsh. “I’m just not sure I understand what that story has to do with me,” I say, and then I cringe. The words sound so selfish coming out of my mouth, and I immediately regret them.

Baba Mysa turns her head and studies me closely. She nods in approval at my acknowledgement of, and reaction to, the selfishness in my statement and she waits a beat before responding.

“It has nothing to do with you, child,” she says firmly. “But you can learn from it.” I nod and wait for her to continue, figuring it’s best to remain quiet at this point.

Baba Mysa sighs, and her fingers begin moving in and out of the yarn on her lap once again. “Life is full of heartache and hardship,” she says. “Very rarely will life make sense, and it will almost never seem fair. But if you remember that pain and heartache aren’t unique to only you, that you’re not the only one mired in circumstances that seem too great to bear, you’ll do much better in life.”

©Kelli Stuart

![]()

Like a River From Its Course is now available wherever books are sold!*

Like a River From Its Course is now available wherever books are sold!*