by Kelli Stuart | Like a River From Its Course, Novel, publishing, Ukraine, veteran's stories, World War II

It’s funny how God puts people together.

Lee and I were freshly married and just beginning our life together in Frisco, Texas. We’d been in town for one week when we got together with a couple whose names I do not remember, nor do I recall how we were connected with them in the first place. I just remember going to lunch and telling these strangers that I needed a way to keep practicing my Russian language so I didn’t lose it.

“Oh, I know the perfect place!” the strange lady said. “There’s a gymnastics academy here in town run by Russians. You should go in an talk to them, and see if there’s a community here to get involved in.”

The next day, I visited the World Olympic Gymnastics Academy for the first time. Sometimes, I chuckle at my tenacity. I walked in and told the receptionist I was looking for someone who would speak Russian with me. She looked at me as if I had two horns growing out of my head, then led me into the gym and introduced me to Valeri Liukin and Evgeny Marchenko.

“I want to practice my Russian,” I said. Valeri cocked his head to the side slightly and smiled.

“Do you know anything about gymnastics?” he asked.

It just so happened I had been a competitive gymnast as a kid, and had coached on and off through high school and college. I nodded my head and he looked at Evgeny.

“Do you want a job?” he asked.

And so it was that I began working at WOGA not because I was looking to be a coach, but because I was looking for Russian speaking community. For two years, the coaches at WOGA took me under their wing, inviting me to parties, answering my incessant questions, helping me understand the nuances of the language I loved, and so much more.

They were my people, and it was them I was saddest to leave when we moved away.

The year after we moved, I contacted Evgeny with yet another odd request.

“I’m going to Ukraine to interview veterans for a book I want to write. Do you have any contacts there who can help me?”

It so happens, Evgeny’s mom lived in Vinnitsya, Ukraine, and within a week it was all set up for me to spend a few days with her.

A pregnant, sick Kelli, with Victoria and her table full of food!

Victoria Marchenko welcomed my mom and I into her home with open arms, and a table brimming with food. I was sick when I arrived, having picked up a terrible cold on the trip, and she immediately took it upon herself to cure me with tea and vereniki (think dumplings filled with meat – yum!).

Victoria was a true gem. She mothered me for the next two days as she took me around town, introducing me to some of the most fascinating people I would meet in all my travels.

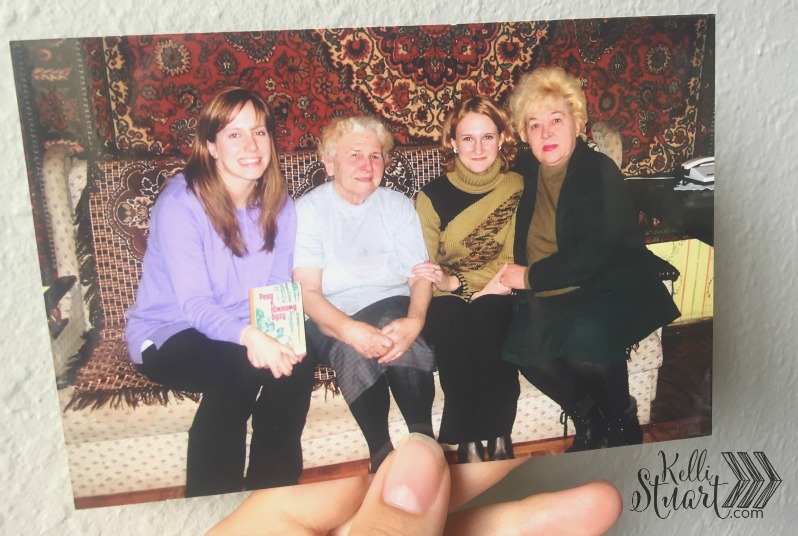

She took me to the home of her friend, Elizabeta Semenova, a woman who worked as a partisan and whose experience became central to the story of Luda.

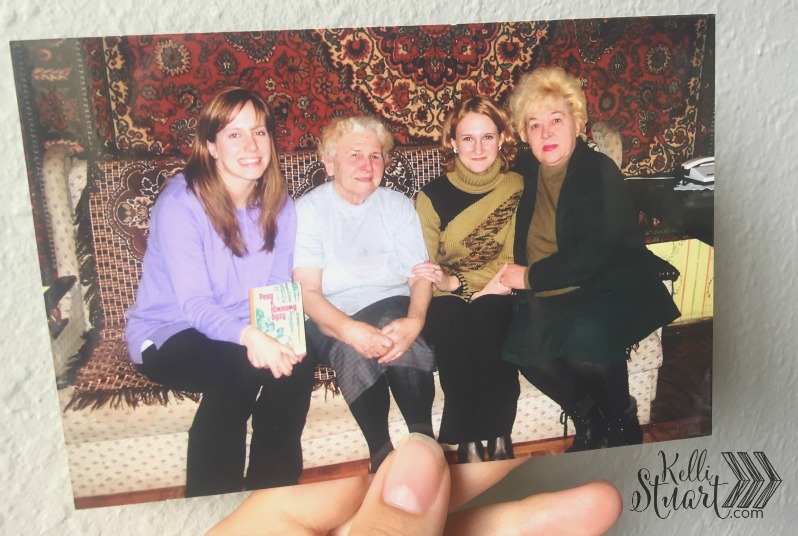

Me, Elizaveta, my dear friend Sveta, and Victoria in Elizabeta’s home.

She took me to a group of veterans who were one of the liveliest bunch of men I’ve ever met. They told their stories one at a time, and Victoria sat in the corner taking it all in. You could tell she was respected and admired within her community, and I felt a sense of pride just being in her presence. Somehow I knew I’d found a very special lady.

Victoria also told me about Vervolfy, Hitler’s underground bunker built just on the outskirts of Vinnitsya. Now just a meadow with no seeming significance (though the site has never been excavated, which gives it a mysterious quality), Victoria made sure I understood the gravity of what occurred at that place. Her description was so vivid and passionate that when I finally visited the site in person, I felt a hallowed awe for the men and women who died there.

This book wouldn’t have come together the way it did if it weren’t for Victoria Marchenko.

It wouldn’t have come together at all if I hadn’t been to audacious to walk into that gym so many years ago and just ask someone to talk to me. I mean, really – WHO DOES THAT?!

What a lovely thing it is to see the tapestry of this project woven together for such a time as this.

Speaking of the book, it’s time for another GIVEAWAY!

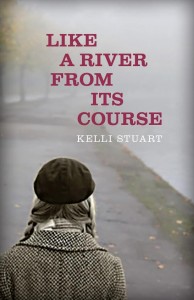

Litfuse Publicity Agency started their blog tour for Like a River From Its Course, and you have the opportunity to win big! They’re giving away a copy of the book, a Kindle Fire, a Kindle Fire case (winner’s choice), and a $30 Amazon gift card. And the best part is, it’s super easy to enter!

Don’t let this stop you from purchasing the book, though! Order your copy of Like a River From Its Course* today and find out why people are calling it the best book they’ve ever read.

If ever there was an opportunity for me to honor the memories of Victoria Marchenko, and all the men and women to whom she introduced me, this book is it.

Thanks for honoring them with me!

*affiliate link included

by Kelli Stuart | Like a River From Its Course, Novel, Ukraine, veteran's stories, World War II, Writing

I spent the better part of two days last week tearing my house apart.

I was on a search for a photo. I could see the picture in my mind, but it wasn’t any of the places I imagined I would have put it. The up side to all this searching was the natural consequence of cleaning out drawers that desperately needed to be cleaned.

I finally decided to check the attic, even though I knew for certain the photo couldn’t be up there. Hadn’t I seen it recently?

I opened the first album I found and gasped. There she was, just as I remembered her, staring up at me with those kind, smiling eyes.

Ladies and gentlemen, I would like to introduce you to the real Maria Ivanovna.

Maria’s story is fictionalized in my novel, though of all the storylines, hers stays truest to the real life plot. Some of it is fictionalized based on other stories that I gathered, but the skeleton of the entire book started with this woman right here:

Isn’t she just lovely?

And as I mentioned in the post about Baba Mysa, that character was also a composite of this real and lovely woman who entrusted me with her story so long ago.

After I found this one photo, I was hungry for more, so I reached out to my dear fried in Ukraine, who also happens to be Maria’s granddaughter, and I asked for more photos.

Alyona took me into her home when I was 20 years old, and she gave me her bedroom for four months so that I could study Russian. Every day, I’d walk from her little apartment on Shamrila Street to the train station, and I’d make the hour long trek to the Institute of Foreign Languages for my classes.

It was one of the grand adventures of my life.

The photos Alyona sent me brought tears to my eyes, because they brought not only the character of Maria Ivanovna to life, but they also gave me more of a visual for the real Maria.

Maria as she was making her escape from Germany.

Maria after the war.

Maria and her husband.

It’s easy to forget sometimes that history is real people. It isn’t just stories. When we’re so far removed from an event that is now immortalized in film, television, and history books, we overlook the before and after of all this history.

Maria had a history before the Germans forced her into slave labor, and she had a future after she returned. She was more than the moment of her captivity. She was real, and she was a delight.

The final picture I found was taken on the night that I met Maria face to face. It was 1996, and we were in Kiev, Ukraine. I had been invited to have dinner at Maria’s place, and while there, she shared her full story with me.

That was the birth place of Like a River From Its Course.

Now, before I show you this picture, I would like to sincerely apologize for what I’m wearing. I don’t ever remember owning such a sweater. It appears I let Mr. Rogers dress me for that evening.

You’ve been warned.

Kelli (in a most unfortunate sweater), and Maria. April, 1996.

History is real people, and as you read my book, I hope you will remember that these are more than just stories. These were lives. These were men and women who refused to be defined by one moment in time.

In the wake of all that’s occurred in our own country this week, it’s good to remember that we are more than one horrific event. We can still learn from history. We can honor the fallen, pick up the pieces, and refuse to be defined by that terrifying moment.

History is real people, and history is happening even today.

Like a River From Its Course is now available wherever books are sold!*

Like a River From Its Course is now available wherever books are sold!*

Also, if you’ve read the book, would you be so kind as to leave a review on Amazon or Goodreads? Those are kind of a big deal. *wink*

Thanks, everyone!

*affiliate link included

by Kelli Stuart | Like a River From Its Course, Novel, Ukraine, veteran's stories

We sat around a long table inside a very small room. It was hot and loud, all the sounds and smells mixing together in a cornucopia that threw my senses into overload.

They’d made pizza for me, because I’m American and they felt pizza would be a comforting reminder of home.

They weren’t wrong.

I’d been invited to this private meeting because I’d shown such an interest in Maria’s story. I’d peppered her granddaughter, Alyona, with so many questions that she finally offered to bring me to her grandmother so I could ask my questions in person.

As soon as I met Maria, I fell instantly in love, and it wasn’t hard to see why. She was a small woman, her bright silver hair pulled back into a loose bun. Her blue eyes sparkled when she spoke, and the lines that crinkled her face revealed years of tenderness and laughter.

Her family called her Baba Mysa, an affectionate term combining the tender form of “grandma” with a word that translates “little fly.” When Baba Mysa spoke, the room got quiet. We wanted to hear what she had to say, wanted to soak up her grace and wisdom.

As I wrote my story, I knew I wanted to tell Maria’s story, but I also wanted to honor the Maria that I knew – the grandmother who exuded warmth and strength. I wanted readers to know both versions of the same woman.

The character of Maria Ivanovna is loosely based on my Maria’s story of survival during those dark years in the war. But the character of Baba Mysa is based upon the older, wiser Maria who gifted her story to me.

And I fell madly in love with this character.

Baba Mysa’s background and story is entirely fictional, but her mannerisms, humor, and strength are not. Baba Mysa exudes dignity, hope and survival. I adored writing this character because through her I was able to honor the woman who endured indescribable hardships and refused to dwell on them.

Today, I’m sharing a brief excerpt from my upcoming novel, Like a River From Its Course. In this section, Baba Mysa is sharing her story with Luda, encouraging her not to get wrapped up in the pain of the past, but to dwell in the beauty of the present.

For more information on the book, visit the book page where you’ll find more links to some of the history that inspired these stories, as well as Pinterest-worthy images, and links where you can preorder your copy!

Be blessed, friends.

Like a River From Its Course: An Excerpt – Baba Mysa

Baba rocks slowly and rhythmically back and forth in her rocking chair, her hands moving in perfect rhythm. The yarn begins to take shape, a perfect hat for Sasha’s tiny head.

“I want to tell you a story, Luda,” she says. Her voice is soft and warm. I sigh as I melt back into my chair nodding my head in concession.

“I was born a long time ago, deep in the heart of Ukraine. My father was a farmer, and my mother was his strong and doting wife. I grew up among the rows of wheat and vegetables that my father grew.”

Setting her work in her lap, Baba Mysa leans back and a serene look overcomes her face.

“I can still smell the scent of the cherry trees that surrounded our small country house. I feel the cool air of fall and remember every bit of peace as I walked along behind my father through the rows of potatoes. Everything about that time was simple and sweet.”

She pauses, and I look at her impatiently. I enjoy hearing a bit about her childhood, but I don’t understand what she’s trying to communicate.

“When I was ten years old, my father took me into the fields to harvest the potatoes. For hours, we pulled plants from the ground and filled baskets, which we lined up in a long row at the edge of our field. My parents would clean the potatoes later in the day and sell most of them in the local market. At least, that’s what they did every year before this one.”

Baba Mysa’s voice trails off, and I study her face. Her eyes are bright and clear as she stares hard at the wall, the memory playing out before her on an invisible stage.

“On this day, as father and I neared the last row, he told me a joke. I don’t remember what the joke was, but I wish I did, because those were the last words he ever spoke to me.”

My eyes focus in tight as I absorb the shock of her story. Her eyes remain still on the wall, wide and pained.

“As I laughed at his silly words, a man on a large horse rode quickly up to us. He shouted something about danger coming and told us to run. My father told him to take me, and the man scooped me up and fled with me. My last vision of my father is the sight of him standing in the fields, covered in dirt, his arm up in a solitary wave good-bye. I never saw him again.”

It’s quiet for some time as I process Baba Mysa’s story. She wipes her eyes several times, and I don’t speak in order to give her time and space. After a few moments, I finally work up the courage to say something.

“I’m so sorry, Baba,” I say quietly. “I’m so sorry you had to go through that terrible ordeal. But . . .” I pause, unsure of how to proceed without sounding harsh. “I’m just not sure I understand what that story has to do with me,” I say, and then I cringe. The words sound so selfish coming out of my mouth, and I immediately regret them.

Baba Mysa turns her head and studies me closely. She nods in approval at my acknowledgement of, and reaction to, the selfishness in my statement and she waits a beat before responding.

“It has nothing to do with you, child,” she says firmly. “But you can learn from it.” I nod and wait for her to continue, figuring it’s best to remain quiet at this point.

Baba Mysa sighs, and her fingers begin moving in and out of the yarn on her lap once again. “Life is full of heartache and hardship,” she says. “Very rarely will life make sense, and it will almost never seem fair. But if you remember that pain and heartache aren’t unique to only you, that you’re not the only one mired in circumstances that seem too great to bear, you’ll do much better in life.”

©Kelli Stuart

by Kelli Stuart | News, Novel, Ukraine, veteran's stories, World War II

She sat across from me, her mouth turned up into a soft smile. With eyes crinkled at the edges, and a gentle lilt to her words, she took me back into the recesses of her memory.

It was 2003, and I was in Vinnitsya, Ukraine. Elizabeta Yepifanova agreed to meet with me on a brisk, March morning, and over a spread of tea and chocolates, she invited me into her story.

Elizabeta was sixteen when the Nazis invaded Vinnitsya. Unable to enlist in the Red Army, she found herself stuck, forced to live under the invader’s imposed law, and unwilling to stand idly by while young boys with cropped hair took over her home. She wasn’t, of course, the only one left heated with indignant pride.

A group of young men and women like herself formed a quiet group. Meeting weekly in the hushed corners of the local library, this pack of partisans made it their mission to fight a different kind of battle with the Nazis.

“We fought a psychological battle,” she told me. The interpreter sat quietly by my side, whispering Elizabeta’s every word like it was a sacred secret, and perhaps it was.

“We wanted those boys to know that though they had physical might, they did not have the power to break our spirit.” She tossed me a mischievous glance. “And we won that psychological battle.”

Not content to subject themselves to the Nazi’s rules, Elizabeta and her comrades devised secret plans to keep the German soldiers ever aware of their own infallibility. “The Germans were afraid of us,” she laughed. “We were unpredictable and shrewd. They never knew where we would strike next.”

“I got very close to a Nazi once,” she continued. “It was the most dangerous mission I participated in. But I was successful. Of course I was successful,” she chuckled. “I’m here talking with you now!”

Late one evening in 1943, Elizabeta and her friend, Sophia, walked to a nearby market where German soldiers were known to congregate, and they openly flirted with two of the Nazis.

“We got those boys to come with us easily,” she said, eyes twinkling. “We didn’t speak German, of course, and they knew very little Russian, so most of the communicating took place with gestures. But if you can believe it, I was quite beautiful then, so it didn’t take much to convince them to follow us.” I smiled, because I could believe it. Behind the wrinkles and the grey hair, Elizabeta Yepifanova had striking features.

“We lured them to our safe house and had them take off their coats in the front hall. When we saw their guns, we pretended shock and fear, and those boys were quick to remove the weapons and lay them down. They thought they’d get something from us that night, but we were the ones who got lucky.” With a slap of the knee, Elizabeta let out a hearty laugh.

by Kelli Stuart | Novel, Travel, Ukraine, veteran's stories, World War II

“It’s not fair! You’re just…you’re putting to much pressure on ME!”

With face in hands, the child ran from the room and slammed the door leaving me bewildered in the kitchen. All I asked was for help putting the dishes away.

Too much pressure?!

With a shake of my head, I left the dramatic child alone for a few minutes, because we both needed a time out. I pulled the box of old photographs down off the shelf and began rifling through. Sometimes memories bring a soothing balm to the rocky places of the present day.

When I came across the pictures from my trip to Ukraine in 2003, I let out a little yelp of joy. I’d been looking for those pictures for weeks, wanting to jog my memory of the events that so clearly marked the path for my book. I ran my fingers across the photographs, willing myself to remember the moments.

2003: A Meeting with veterans in Kam’yanets Podilsky, Ukraine.

Some of them seemed vague. The time I spent in that country was a whirlwind, and I was rather pregnant great with child, so not all the memories were cohesive. But a few were, and as I sifted through them, my dramatic child came and sat by my side.

“Who’s that?” The voice was soft, with the hint of apology floating at the edges.

“Those are men who battled evil,” I answered. “Those are men who know pressure. Real pressure. They understood suffering.”

I turned and offered a crooked smile. “Those are men who probably didn’t enjoy cleaning the kitchen, either. But they wouldn’t call it pressure. Maybe just more of an annoyance?”

A smile in return. The ice was breaking just a bit.

“Do you remember their stories?”

I looked carefully at the photo. “Not specifically,” I replied, “but I have them all written down. I’ll look them up later.”

“Why are their stories so important?” The innocent question was met with a quizzical stare, and all I could offer was a shrug at that moment. I couldn’t formulate the right answer, so I let the question hang in the air.

“Why are their stories so important?”

Long after the kitchen was cleaned and the house grew silent as the sun set low, I continued to mull over that one, simple inquiry.

Why are their stories so important?

These men are not American. Their stories and experiences tell of not only a time unfamiliar to most of us, but also a culture. Why is it important to tell their stories? Why should you care? Why should I care?

It’s said that the shortest distance between two people is story, and if that’s true then the question we should be asking is why wouldn’t we care?

These men stood up before their peers, and before a strange American girl, and they shared their stories. They shared them because they wanted me to know, and they wanted you to know.

They wanted us to see that the distance between us and them isn’t really all that far after all. We share the common longing for peace in a world that often quakes with violence.

We were all uniquely designed by a common Creator, and that design draws us together even if the miles, the language, and the landscape of our lives looks different.

So why are their stories important? Why should you care about the histories of a handful of men and women from half a world away?

Because their stories offer the connection between then and now, and in a time when evil runs rampant and we watch the world with wide eyes, a reminder of man’s capacity to overcome evil is beautiful, indeed.

Because their stories offer the connection between then and now, and in a time when evil runs rampant and we watch the world with wide eyes, a reminder of man’s capacity to overcome evil is beautiful, indeed.

In the months leading up to the release of my book, I will offer more background on the stories and events that inspired the novel. In the meantime, visit the War Stories page to read the histories of the four people who most impacted me as I researched this novel.

![]()

Like a River From Its Course is now available wherever books are sold!

Like a River From Its Course is now available wherever books are sold!

Because their stories offer the connection between then and now, and in a time when evil runs rampant and we watch the world with wide eyes, a reminder of man’s capacity to overcome evil is beautiful, indeed.

Because their stories offer the connection between then and now, and in a time when evil runs rampant and we watch the world with wide eyes, a reminder of man’s capacity to overcome evil is beautiful, indeed.